It’s launch day. This issue marks the first official article of the new-and-improved Enthusiast. We hope you’ll enjoy, and look forward to bringing you more idiosyncratic praise every Thursday. In the meantime, if you’re just finding us, subscribe to get weekly articles from our cabal of enthusiasts, right in your inbox:

I have a great love of paperback books. Sure, we all enjoy the angular heft of a leather-bound tome, but the trim, aerodynamic lightness of a paperback implies a certain readiness for the circumstances under which reading more often occurs: rushed, piecemeal, and frequently encumbered. Thus, while my high school days were spent scouring used bookstores for illustrated Nineteenth-Century hardbacks, my adult years have seen me lingering in a different aisle. I've grown especially fond of midcentury American editions from imprints like Noonday, whose geometric cover designs and restrained palettes have an elusive beauty about them, and look all the more alluring when they've browned with age along the fringes.

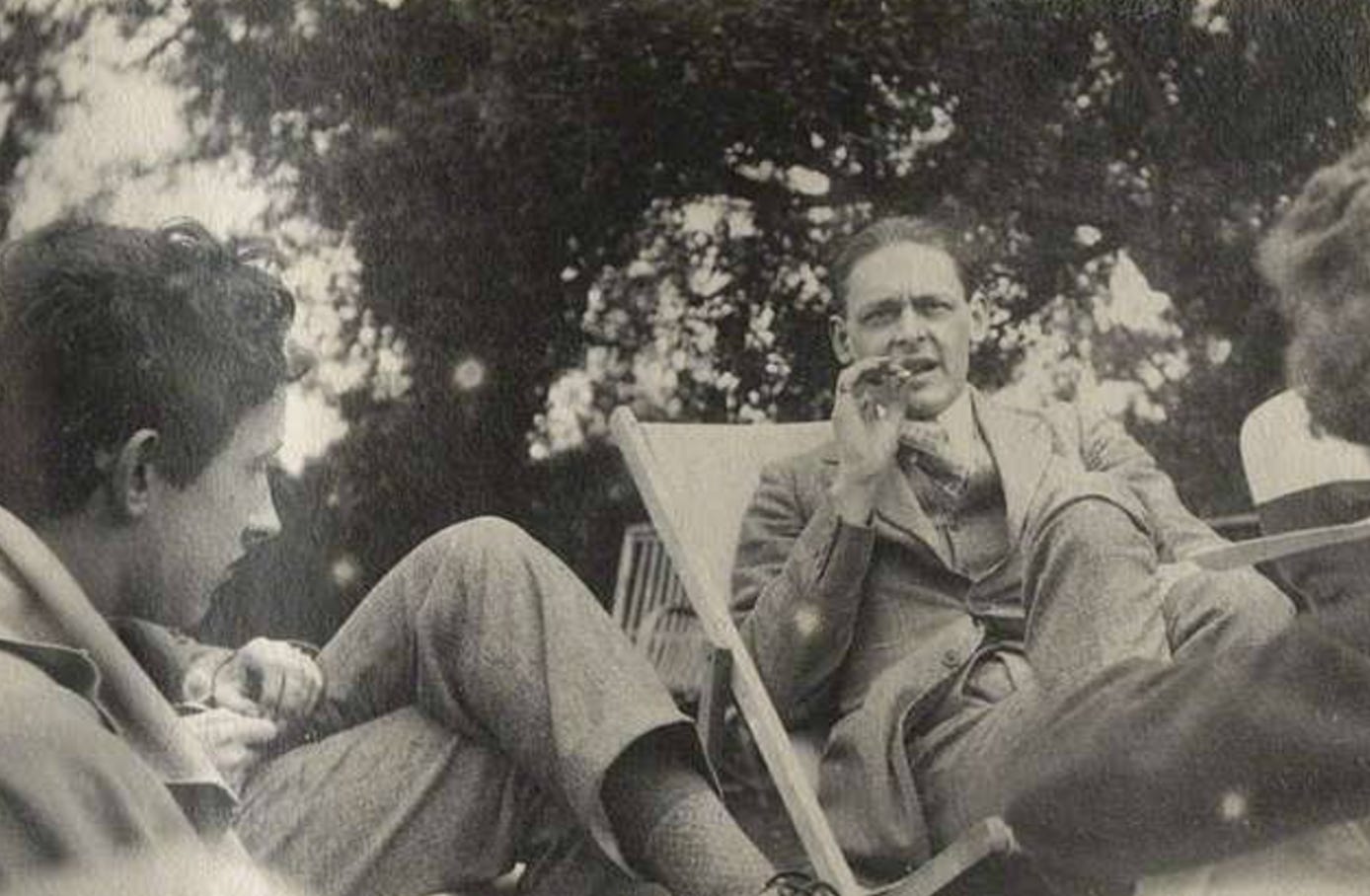

I was therefore very pleased when, almost a decade ago, a retiring colleague gave me a cardboard box full of old paperbacks by T.S. Eliot, that great and enigmatic modernist poet born 136 years ago today. One particular volume caught my eye: To Criticize the Critic, a collection that gathers some of his best prose writing about literature and education. Its stark cover in yellow, black, and cream, already speckled with dignified age, called to me, but I didn't manage to make time for it until recently.

When I finally pulled it from the shelf, I was rushing out to teach a college night class. Shoved in my briefcase, the book waited patiently until, having launched my students on an in-class essay, I pulled it out and cracked the cover—or rather, shattered both the cover and the spine, since the binding was so desiccated from long neglect in my study that, when I opened it, the volume split with an audible crack into a tumbling sheaf of papers, mottled as birch bark and as ungainly as a pile of leaves. I’m inclined to leave it like this, an aggregate of disconnected parts that can only be held together by an act of will—a parable about something that Eliot himself considered often and genuinely feared: the state of fragmentation. He was driven, above almost anything else, by the impulse to unify, which is perhaps why our willfully fragmented age tends to be afraid of him.

Indeed, if we know anything about him at all, most modern people picture Eliot as the arbiter of Modern angst, the Wastelander, the uber-critic; a bony, disconsolate crow hunched behind a banker’s desk doling out literary judgments like eviction notices with a flourished quill. And he was certainly capable of some of the most withering dismissals in Twentieth-Century criticism, like this one about Edgar Allan Poe: "That Poe had a powerful intellect is undeniable: but it seems to me the intellect of a highly gifted person before puberty." If Poe had not already died in a snowy ditch in Baltimore long before, this comment would probably have killed him. It's the sort of thing that would be painful coming from anyone but, coming from an intellectual eminence like Eliot's, gains enough momentum to be deadly.

Perhaps because of this diamond-sharp critical edge, Eliot tends to come off as unapproachable. I still remember someone in my graduate seminar at the University of Edinburgh—one of the only other Americans in the course—calling Eliot "a cold poser." Given that Eliot was born in St. Louis but ultimately renounced his American citizenship, and even adopted a dubious anglophone accent, my classmate's patriotic thorniness can be forgiven. But the real Eliot, far from some becloaked Dickensian villain, was a man who felt so keenly indebted to the beauties of Western Literature that he spent his whole life trying to understand the gift—and to repay it. We might doubt his success on the former point, but we can hardly doubt the latter. And, though they’re not as famous as The Four Quartets or "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," the essays in To Criticize the Critic are ample proof, in and of themselves, of Eliot's passionate, compassionate inner being, not to mention his superlative skill as a prosodist.

Take this passage, from that same essay about the influence of Poe, "From Poe to Valéry." In it, Eliot explains the debt that all detective literature owes to the author of "The Black Cat" and "The Raven." Warming to his point, he froths himself up to the height of his critical powers:

Conan Doyle owes much to Poe, and not merely to Monsieur Dupin of ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue.’ Sherlock Holmes was deceiving Watson when he told him that he had bought his Stradivarius violin for a few shillings at a second-hand shop in the Tottenham Court Road. He found the violin in the ruins of the House of Usher.

Now, this is about as good as a critical image can get. It’s memorable, metaphorically resonant to the point of poetry, accurate to the relationship he’s trying to explain, and vivid without being overwrought. Sure, it's closely followed by that stinger about Poe's prepubescent intellect, but that harsher comment only arises from Eliot trying to explain a very real deficiency he noticed in the tone and range of Poe's work. It's not so much a spiteful jab as a guileless diagnosis, tinged with human pity, and perhaps all the more damning for that.

In fact, what we find on evidence everywhere in "From Poe to Valéry" is a flexible, humane intelligence that feels indebted to the world of letters. He is operating not from a military pillbox but from a high outpost, eager to use his long view to provide aid where he can. Compassion is the motive force. "There is a certain flavor of provinciality in [Poe's] work," Eliot goes on, "in a sense in which Whitman is not in the least provincial: it is the provinciality of the person who is not at home where he belongs, but cannot get anywhere else." The note of sympathy is audible here. He is not scowling at Poe's provinciality, he is frowning at the thought of what Poe might have been had he enjoyed better advantages. You might argue that this pity is founded on a certain Boston-Brahmin superiority, but the accusation would be unjust. After all, the nobility is at its worst not when it ceases to have advantages, but when it ceases to use them for the common good. And all of Eliot's great intellectual wealth was put to the service of his fellow readers. He was not a cultural banker, nor a prodigal: he was a curator and acolyte, painstakingly scraping the detritus of time off of every masterpiece that came into his care, and producing many of his own along the way.

Eliot once wrote of Milton that no poet had ever learned so much, yet so completely justified that learning. But Eliot forgot to credit another writer of the same quality and caliber—himself. Here on his birthday, it is worth revisiting the wealth of even his lesser-known writings. If we do, we'll not only find him a good author, but something even rarer and more wonderful: good company.

I haven't read Eliot in years. A good reminder and encouragement. Congrats on the launch! I'll look forward to Thursdays.